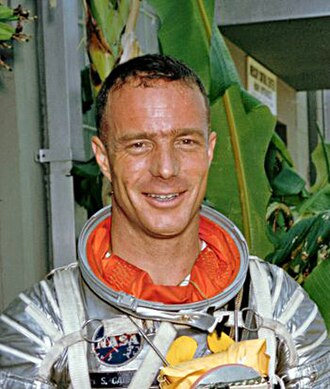

Malcolm Scott Carpenter (born May 1, 1925, in Boulder, Colorado, died October 10, 2013, in Denver) was an American astronaut, naval aviator, engineer, and United States Navy lieutenant commander. He completed studies in aeronautical engineering at the University of Colorado. In 1949 he entered the United States Navy, and in 1951 he finished training as a naval aviator at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis. During the Korean War he flew missions in twin‑engine Lockheed P‑2V Neptune patrol aircraft, which by that time were already equipped with two additional jet engines. In 1954 he was sent to the Navy test pilot school at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, and after completing the course he flew as a test pilot and also served aboard the aircraft carrier USS Hornet.

On April 2, 1959, NASA selected him for the first group of astronauts, intended for spaceflights in the Mercury program. On February 20, 1962, he served as backup for John Glenn during the first orbital flight of a United States citizen. For the next orbital mission Donald “Deke” Slayton was initially assigned, but because of heart problems he was removed from the Mercury‑Atlas 7 crew, and his place was taken by Carpenter.

The mission launched on May 24, 1962, with Carpenter strapped into the capsule he named “Aurora 7.” As in previous Mercury flights there were problems with the environmental control system, and the cabin temperature was higher than planned. During the flight the astronaut determined the spacecraft’s attitude using the stars, photographed the Earth and objects in space, studied the effects of weightlessness on his body, and carried out numerous radio communications with fourteen ground stations along the flight path. At the beginning of the third orbit, in accordance with the flight plan, he took a colored balloon 90 centimeters in diameter from its container and deployed it outside the capsule on a 30‑meter tether; by observing it he investigated the drag produced by the rarefied upper atmosphere, tested his ability to judge distances, and evaluated the visibility of the balloon’s colors. While in orbit he ate a meal consisting of compressed fruit—almonds, dates, and nuts—along with chocolate and bread, making him one of the first astronauts to consume solid food in space.

As “Aurora 7” approached the American coastline from the west for the third time, preparations to leave orbit began. At 18:17 a “Retrofire” signal was transmitted from the ground, commanding ignition of the retrorockets, but the engines did not fire and the spacecraft continued to drift eastward. Carpenter was immediately ordered to fire the rockets manually, which led to a 15‑second delay, and additional navigation inaccuracies caused the capsule to enter the atmosphere at only 25 degrees instead of the planned 34. As a result, splashdown took place roughly 400 kilometers farther downrange than intended. For about 45 minutes there was a complete loss of radio contact with the astronaut, and nobody on the ground knew what had happened to him. After a successful splashdown Carpenter left the capsule and transferred to a life raft; at 19:20 he was spotted from an aircraft, and half an hour later rescue divers were dropped, but he still had to wait another hour and a half to be hoisted aboard a helicopter. Only after the flight did the reasons for this delay become public: according to a letter from former head of the U.S. air‑sea rescue service General Dubose to several senators, aircraft could have rescued the astronaut an hour and a half earlier, but naval command did not allow Carpenter to be taken aboard a plane because the U.S. Navy wanted to recover its officer itself.

On his only spaceflight Carpenter spent 4 hours, 56 minutes, and 5 seconds in space. In 1964 he was seriously injured in a car accident, suffering a complicated fracture of his left arm; despite surgery, doctors were unable to restore full mobility, which cast doubt on his further participation in spaceflights. Given this situation he was reassigned to lead undersea research projects under the auspices of the Navy. In 1965 he spent 30 days, from August 27 to September 26, in the Sealab II underwater habitat off the coast of California near La Jolla.

He left the astronaut corps on August 10, 1967, continuing to work for NASA and later serving as director of undersea operations for the U.S. Navy. In 1969 he retired from active duty and founded his own company, Sea Sciences, Inc., devoted to developing programs for the use of marine resources and the protection of the marine environment. In this work he collaborated, among others, with oceanographer Jacques‑Yves Cousteau.